This exhibit review by Veronica C. Fuentes is her output for our Art Criticism Writing Workshop last September 2024.

THE VALUE OF GOLD: LOOKING AT AYALA MUSEUM’S EXHIBITION “Reuniting the Surigao Treasure: From the Collections of the Ayala Museum & the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas”

by Veronica C. Fuentes

Gold has been hailed as one of the most precious metals: it is dense, malleable, and aesthetically pleasing. It is also a good conductor of electricity and can be found in nature. Its uses vary from ornamental (in the form of jewelry or an accessory attached to an artifact) to fiscal (i.e., the gold standard, where currency valuation is dependent on quantity of gold), social (gold as indicative of stature and wealth), and even cultural (different civilizations use gold as part of marking special life events from birth to death).

The role of gold in Philippine society has been well-documented in the Boxer Codex, the late 16th century Spanish manuscript detailing the culture of the peoples in Asia, from the point of view of the anonymous scribes who documented their stay in the area. Here, illustrations of various precolonial ethno-linguistic groups were featured in full detail, featuring traditional garb and accessories, including gold.

Gold has been abundant in precolonial Philippines, making it a ubiquitous fare. Gold was used to perform various utilitarian purposes such as external body ornamentation, clothing, accessories, vessels as daily wares, weapons and currency for trade. Gold was also indicative of social status. Higher ranking individuals would have had the most number of the purest (dalisay) forms of gold. They would have had the right and privilege to wear gold of the highest quality. The more gold you had on your body, the more power you hold in society. The most prominent figures would have had the highest quality of gold as heirlooms and dowry.

Gold has been the highlight of Ayala Museum’s special attraction for its 50th year (its golden year since its establishment in June 1974). Titled “Reuniting the Surigao Treasure: From the Collections of the Ayala Museum & the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas”, the exhibition combines the institutional collections of two powerhouses of the private and public sphere with rich acquisition of Philippine material culture.

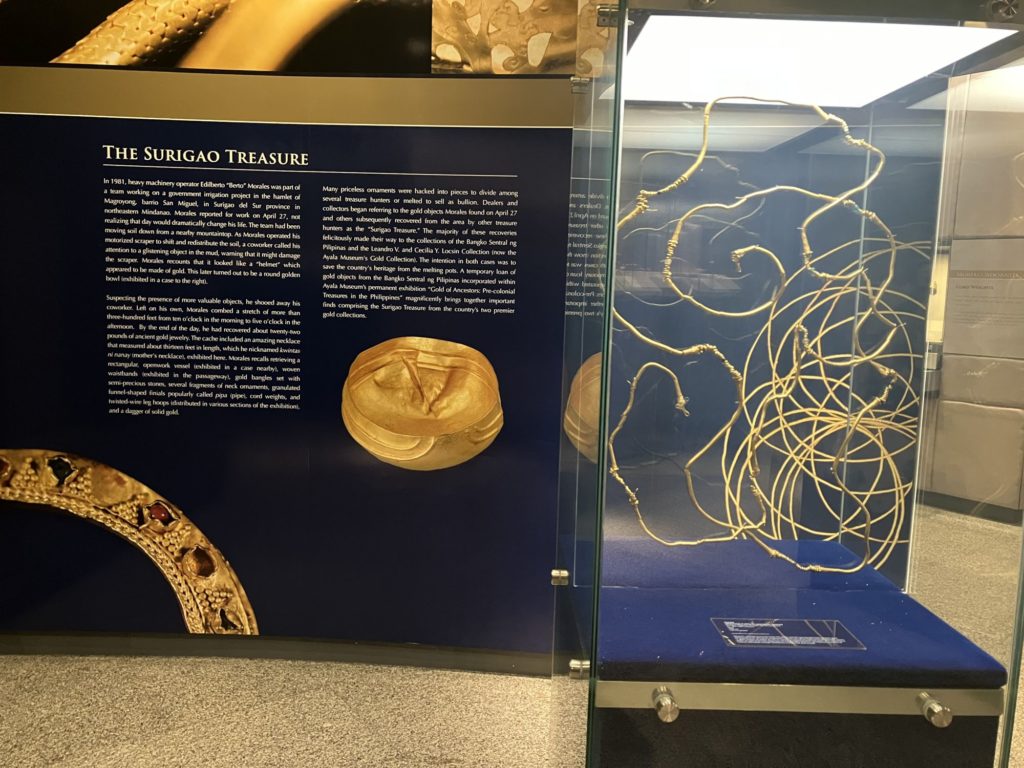

(Left) Wall Text. (Right) Kamagi, (long string of different beads, kwintas). Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province. Ca. 10th – 13th century. Gold. 453 cm. 1,377.5 grams. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection. Spanish colonial accounts from the early contact period describe opulent gold jewelry worn by the local inhabitants. Chiefs are described wearing multiple layers of gold chains, as many as ten or twelve wrapped around the neck. This impressive chain on loan from the collection of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas consists of twelve individual kamagi necklaces connected end to end.

Ayala Museum’s gold collection comes from the magnanimous donation of National Artist Leandro Locsin and his wife and archeologist, Cecilia Locsin. The couple’s advocacy of recovering objects within their archeological context paved the way for the Northeast Mindanao Salvage Project which mapped and approximately dated the gold objects they retrieved. This project ran in alignment with the museum whose aim was to “to empower Filipinos with a deep appreciation for our traditions, art, history & culture”. The Locsins and Fernando Zóbel (the progenitor of the museum’s vision, later on actualized by the Ayala Foundation) made such a strong partnership that the breadth of the gold mounted by the Ayala Museum was pronounced “perhaps the country’s greatest tangible cultural asset and can stand in comparison with any other assemblage of gold artifacts in the world” by Southeast Asian scholar Dr. John Miksic.

On the other hand, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is a government mandated entity tasked to strengthen the nation’s gold reserves by buying gold from local miners. This ensures a thriving mining industry with job security. BSP’s wide treasure trove includes a considerable amount from the bulk of gold known as the Surigao Treasure, the point of reference for this exhibition.

The Surigao Treasure, the bulk of gold featured in the eponymous exhibition is a fascinating subject, since it was discovered by chance, and the enormity of quality and quantity of the haul points to a once golden era of the Philippines. On April 27, 1981, Edilberto “Berto” Morales (a heavy machinery driver working on a government irrigation project in Magroyong, barrio San Miguel in Surigao del Sur) accidentally came across what seemed to be a metal helmet while operating his motorized scraper to move mud. He inspected the object and found glistening gold objects spanning about 100 meters containing 10 kilograms of ancient gold jewelry. Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms detailed the objects he dug up.

The treasure included an amazing necklace that measured about 13 feet or 4 meters in length … bangles with colored stones of pink and green, several fragments of suso (shell-shaped) ornaments, granulated funnel-shaped finials popularly called pipa (pipe), cord weights, twisted wire leg hoops, woven waistbands, a helmet or bowl, and a dagger of solid gold.

Important pieces in the Surigao Treasure, both in the Ayala Museum Collection, include the kinnari and a golden halter. The kinnari is a three-dimensional anthropomorphic design described by Florina Capistrano-Baker as “a composite celestial female with a human head and torso, and the legs of a bird” in Indian mythology, implying Buddhist influences in precolonial Philippines. The latter, the golden halter (arguably the most important piece in the whole trove that is the Surigao Treasure), weighing 4 kilograms, is the only known example in the world. It is also presumably an ornament made for the use of a prominent datu (chief or community leader) during the precolonial period. The book Philippine Ancestral Gold describes this as:

The massive, square-sectioned cord consists of an inner loop-in-loop chain encased by four other chains interwoven with segmented beads and held together by gold filaments on its four sides. One end terminates in a big loop through which the opposite bejeweled terminal (now missing) was drawn. This stunning treasure gives eloquent evidence of an affluent elite class with strong affiliations to Hindu culture and of the astonishing quantity of gold available to artisans at the time.

Kinnari. Surigao. Ca. 10th – 13th century. 12 x 7.5 cm. 178.7 grams. Ayala Museum Collection.

Since the discovery of the Surigao Treasure, there has been widespread looting in Magroyong, affording dealers with artifacts while depriving researchers of valuable archaeological data. Various gold findings guaranteed gold in the market, but not necessarily in their original forms. Gold pieces were hacked or melted to evenly distribute raids amongst parties of treasure hunters.

Edilberto Morales’ life changed after the discovery. He contacted dealers with the help of Fr. Francisco Olvis and definitely became a well-known man. But this had a toll too. His family had a lot of security concerns, including the kidnapping of his children. This forced him to change his name and flee Magroyong. He came back after a few years and agreed to a 2008 interview where he, Fr. Olvis and other locals shared their stories about the wonderful finds in 1981.

The gold objects made their way to the Locsin Foundation (which eventually became the Ayala Museum Collection), Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection (whose proactive acquisition was motivated by the prevention of further destruction of the Surigao Treasure) and numerous private collections.

Ayala Museum already had a permanent collection featuring its own gold collection. The museum grouped gold categorically by use: jewelry and ornamental accessories can be seen in one section, funerary masks together in another, vessels and ceramics congregated together, and floor-mounted gold and ceramic works provided the audience with a visual reference for six archaeological burial sites from Butuan. This same gallery space has been the new site of the new exhibition “Reuniting the Surigao Treasure: From the Collections of the Ayala Museum & the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas”, an attempt to provide a place where the gold treasures can once again merge as one.

Halter. Surigao. Ca. 10th – 13th century. 150 cm. length; 2.7 x 2.4 cm. cross section. 3,860 grams. Ayala Museum Collection. Pronged finial. Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province. Ca. 10th – 13th century. Gold. 3.5 cm. diameter, 1.7 cm. height. 21.7 grams. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection. A paramount datu may have worn this impressive regalia on important occasions, perhaps with a solid dagger suspended from a loop at one end of the cord. Treasure hunters had chopped off the cord’s finial which was originally set with a red cabochon gemstone. Here it is temporarily reunited with its pronged gold setting from the collection of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, though missing its red gemstone.

The gold collection of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas encroached on the space of Ayala Museum by having its own pedestals with glass displays, demarcated well with blue padding cushioning the gold pieces. The plinths were sparse out, situating pieces next to similar ones from the Ayala Museum Collection. Golden sashes were grouped together. Gold ornaments as displayed near its identical brothers from the other collection, both prominently featured near the Boxer Codex reproduction showing how precolonial Filipinos would have worn them.

An educational component in the form of a Probe documentary titled Gintong Pamana was shown on loop, giving context to the history of the Surigao Treasure augmented by interviews and a short walk through of the essential pieces in the exhibition. This video will tell the viewer that among its 1000 gold and ceramic pieces in the collection, 26 were originally from the Surigao Treasure.

The specific objects from the Ayala Museum Collection that pertains to the Surigao treasure inside the exhibition area were not at all emphasized, leaving the viewer guessing where the objects supposed to be reunited with its kin are. One has to scour the exhibition for gold with Surigao as provenance. Even then, this does not validate whether or not it is part of the bulk of the Surigao treasure of 1981. Seeking the 26 pieces would entail so much patience and diligence on the part of the viewer.

This might have been a logistical challenge for the exhibition, as Ayala Museum’s gold collection has a somewhat permanent space for each object, echoing the curator’s vision on how the collection must be viewed. However, a more effective way to introduce the new exhibition is to make a specific area or niche for all the Surigao Treasure. Grouping all pieces together in a particular compartment would highly emphasize the Surigao Treasure as a whole. Giving a definitive space for the objects will minimize confusion and would be able to provide a more systemic way of looking at the artifacts.

(Left) Kinnari. (Right) Neck Ornaments from the Surigao Treasure.

The exhibition’s most remarkable feat is the tangible unification of two golden pieces that makes up a golden regalia. The golden halter (mentioned above) in the Ayala Museum Collection was arranged together with its finial (missing its original red cabochon gemstone) from the Surigao Treasure from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection. This reconnection (literally and figuratively) posits its hold on history.

The physical manifestation that locks in two parts of a whole opens up the trajectory of being: from the demand of its need to its creation, to its use commanded by social norms to its eventual deconstruction (the finial was chopped off by treasure hunters). Then, there goes the individualized traversals of halter and finial leading up to their acquisitions, and finally their coupling in this exhibition.

Moreover, with these objects positioned as intended, history is reinforced in the form of the archive. Illustrations from the Boxer Codex affirms its existence and reintroduces its original form. Its aesthetics that covered a utilitarian purpose prompted its need of a place in the annals of the lives of the Filipino peoples. Yet upon its decline, the same record of its existence authenticates its configuration in a temporal space that is distant, fashioning itself as a material evidence of a retrievable past.

Installation Shot of Video and Wall Text.

In the spirit of the cycle of things, I wonder if Ayala Museum is the best space for the exhibition. The exhibition would have been more meaningful should the gold objects find its way to its source: Surigao. Coming back to the land where the gold was found, shaped and used would have been a wonderful homecoming to two objects needed to be reunited together. It would also be timely as the objects would have resurfaced liked Edilberto Morales, whose accidental discovery of the Surigao Treasure forced him to relocate only to return a few years later. Locals who have been part of the narrative of the golden objects would be able to see them again, demonstrating evidence of the oral history passed down in generations. The objects then would have been a strong cultural capital for the community, and they would have marked a specific historical period and context for people of Surigao. Bearing in mind that the Ayala Museum Collection came from the Northeast Mindanao Salvage Project of the Locsin Foundation, the mounting of the objects in Surigao would also be a good homage to the project that preserved and conserved them.

Another alternative is the National Museum of the Philippines. Not only will it eliminate the logistical nightmare of the transit of gold objects from Luzon to Mindanao, it would also complement the jewelry in the Ethnographic Collection of the museum. Since most of the gold objects are ornamental in nature, it would provide a fresh look in the different media used for accessories in the Philippines. It would also be a good way to establish jewelry making techniques applied in gold working.

These two sites also raise this question. Whose benefit should material culture prioritize: the locality of its production, or the accessibility of the greater public? The former steeps historicity as its main concern, granting the potential of immersive viewing of the works in its natural habitat. The latter evokes education and awareness: a reminder what we once were, what we once had and what we aspire to hold as our identity.

The fact that the exhibition exists in Ayala Museum speaks volumes on an important issue: something happened because someone had a price to pay. Both the Ayala Museum and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas realized the importance of gold, made ways to acquire it, preserve it and maintain its longevity. The Locsins’ donation to the museum would not have pushed through without the rapport and mutual understanding of the collection’s value. More gold would have been melted without the intervention of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. And while this seems elitist, this only proves one point: the valuation of something depends on the way someone sees how invaluable it is. Gold is what you make of it. You just have to manipulate its form to create something priceless. This was the vision of the exhibition: the foresight of conservation of a metal that is conducive to change. Forging worth in gold has potential, and the fact that the Surigao Treasure exists today is proof of its valuation.

Pre-colonial elite in the Philippines wore multiple strands of golden neck chains, wrist ornaments, and anklets to announce their status. This impressive wrist cuff, probably part of a stunning ensemble worn by an important person, is associated with a hoard of gold objects known as the Surigao Treasure discovered in the 1980s.

Having one last look at the exhibition, an uneasiness still lingers inside me. “Reuniting” seems such a big word. The title heavily rests on the idea of a reconnection. The gold objects moved with the currents of the market, having been separated illuminates the zeitgeist of the times. The deconstruction of a set or an object (in the case of the halter and its finial) provided a need or a demand. Is there a point in reunification other than sentimentality? Sure the physical attachment of things become a reminder of a past. But we as a nation have been colonized for far too long by so many peoples. Our gold has been looted by Spanish invaders, razed by the flames or war, and exploited to its limit by the claws of poverty. These reunited gold artifacts will be put up together in the duration of its exhibition run (until 2027). If these objects were to be separated again after being reunited for three years, what was the ultimate goal of the exhibition then?

Instead of reuniting, I propose the change to the term reimagining. In imagination, our once rich society was alive and thriving. The Surigao Treasure was discovered and all would benefit from its abundance. The objects shine its prime, each object proudly glistening with topnotch artistry and craftsmanship. And in reimagining the Surigao Treasure, the collection will be that of the Filipino people. And in its reimagining, we will be able to see the valuable in the invaluable.

SOURCES:

BOOKS

- Boxer Codex (Second Edition) published by Vibal

- Ginto: History Wrought in Gold by Ramon Villegas

- Philippine Ancestral Gold by Florina Capistrano-Baker, John Guy and John N. Miksik

- Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms by Florina Capistrano-Baker

WEBSITES

- https://www.ayalamuseum.org/exhibitions/reuniting-the-surigao-treasure

- https://www.bsp.gov.ph/Pages/AboutTheBank/Facilities/BSP%20Museum%20Collection/Pre-Colonial_Gold_and_Pottery.aspx#banner

—

Photos provided by the author.

Veronica C. Fuentes is a dedicated art and cultural worker with a decade of experience in the field of museums and art institutions: both in the public and private sector. A team player, she has worked with curators, artists, partners, and collaborators on different exhibitions and art endeavors spanning both local and international events. Her interests lie in museum collection, art education and audience engagements in the arts.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc (KLFI).